One of the subjects that is most discussed in regards to muscle building is the issue of how frequently one should work a given body part. When I first started training in 1974 (at the age of 14), many of the bodybuilding magazines printed profiles of the top names at the time, along with descriptions of their workout programs.

In the mid 70s, the trend among the top bodybuilders was to train a body part three times per week. It was common to see an article about Arnold Schwarzenegger, outlining his workout program as follows: Chest, Back and Shoulders on Monday, Wednesday and Friday….. Arms and Legs on Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday. Of course, many of the guys back then would spend half the day in the gym. They would work chest in the morning, their back in the afternoon, and their shoulders in the evening. And those guys were doing 20 sets (or more) per body part. That’s 60 sets per body part, per week. I don’t know anyone who does that today, and I know a lot of people.

The trend today is much less frequency, but high volume. I’ve spoken with numerous bodybuilders who only work one body part per day. It takes them a week of daily workouts to work each of their muscle groups one time – but when they work it, they kill it. “Volume” training is now in vogue – so guys (and gals) do super-high-intensity workouts consisting often times of marathon sets. They work a given muscle until it’s so fatigued they can barely move it – and then they rest it for a week. I’m not saying this is wrong, necessarily. These guys are often huge, so clearly they’re doing something right. However, not all of us are born with excellent genetics, nor willing to take the kind of “supplements”, or as many, as some others are willing to take. But that’s another issue.

Here are the questions we should all be asking ourselves, in trying to establish the ideal frequency of workout.

1. Are 20 sets for a body part in a given workout, four times more productive than 5 sets? Are they even twice as productive (i.e., likely to cause muscle growth)?

2. Does doing 20 sets for a body part require significantly more recovery time, than doing 5 sets?

3. At what point (how many sets for a body part, in a given workout) does “over-training occur”, and what is the consequence of it ?

4. How many days does it take for a muscle to fully adapt to (achieve full benefit from) a given workout ?

5. How many days does it take for a muscle to fully de-condition (lose the benefit) from a given workout ?

So, let’s examine the first question. Assuming our goal is achieve maximum stimulation of a muscle, during a given workout, how many sets is “ideal”? According to some studies (1), sufficient stimulation can be had with an intense few sets. In other words, if we are to believe what these studies suggest, doing more than 3 or 4 sets (after a warm-up set or two) for a body part does not necessarily produce significantly more stimulation for the muscle to grow. It would, however, require more time to recover – which begins addressing the second question. We’ll come back to recovery time in just a minute.

The third question deals with over-training. It’s not clear at what point “over training” occurs, but we can surmise that it occurs sometime after “optimum stimulation”. If optimum stimulation occurs after about 3 or 4 intense sets, over-training might begin to occur after about 5 or 6 sets (assuming they are intense sets). So – let’s speculate a bit – if a person did 15 sets for a particular muscle, in a given workout, he (or she) could be in the over-training zone for the last 10 of those sets. That would mean that those last 10 sets were unproductive – or at least less productive than the first 5 sets. They also used up some precious resources (glycogen and amino acids). And they may have been catabolic (destructive) – causing injury to the muscle – which will require healing time.

The fourth question asks, “how many days after a workout does a muscle reach its optimum benefit?”. This is an important question. If the answer is “two days” or “three days”, it means that by the fourth day, we’ve begun to de-condition. Nothing stays the same; we are always in a constant state of either building up or breaking down. Therefore, the longer we wait – after the peak time of optimum benefit – the more we slide backward toward our starting point.

How many days does it take for a muscle to have lost most or all of the gains it made after the first two or three days? It probably varies from person to person, but there certainly is a specific number of days after which a person has lost ALL of the benefit they gained from the previous workout. For the moment, let’s assume it’s about a week.

The ideal situation, therefore, would be to stimulate a muscle again right at the point of “peak benefit”, and send that muscle’s growth process upward again, before it starts to slide back down. If we wait a day or two (or more) beyond that, we’re likely losing efficiency. It’s like taking two steps forward, one step backward, etc. It would be much better to go two steps forward, and then another two steps forward.

But if a person has over-worked a particular muscle during a workout, it should NOT be worked again after only two days. It might need a full week to recover from the damage incurred during that last “mega-intense” workout. During those extra days of recovery (beyond the day of peak benefit), the muscle will likely be sliding backward – losing some of the benefit it had gained. So the trick is to stimulate the muscle “enough” to cause a stimulus for growth, but not so much that it requires two or three extra days to recover from having been over-worked.

“Enough” stimulation (during a workout) might not look or feel like what we have previously considered to be a “good workout”. This is important to note. Those of us who have been training for quite a while have expectations that may NOT be in sync with what is ideal – physiologically. It may be that “enough” stimulation (during a workout) leaves us wanting more, because we’ve become accustomed to that feeling of total muscle exhaustion. But unless we’ve experimented with a different interpretation of “enough”, we may be over-training. We may be taking two steps forward, and one step backward. It would be better to slightly under-work a muscle, and then work it again sooner, than it is to over-work a muscle, and then lose what we gained during the recovery from that over-intense workout.

This is like the concept of tanning. If you were to lay out in the sun for an “ideal” amount of time (let’s say, 15 minutes front, and 15 minutes back), you could lay out again a day or two later (for the same amount of time), and continue the “productive” process of having your skin get darker, little by little. But if you lay out the first day for an hour each side, it would be “too much” (the equivalent to “over-training”). Now, you would be unable to lay out a day or two later, because you need to heal (i.e., you’re sun-burned). This results in lost opportunity for more productive sun tanning the next day or two, as well as the loss of some of the benefit you gained from that first day of tanning.

The problem is we are usually over-zealous. We want to speed up the process (of tanning, as well as of building muscle), so we tend to do “as much as possible” – believing more is better. If we’re competitors, we believe that training HARDER than our potential opponents will give us an advantage over them. However – even though it may not be as obvious in muscle-building as it is in tanning – there is absolutely such a thing as “too much”, and it is counter-productive.

Clearly – for the purpose of bodybuilding – the solution would be less volume (i.e., less muscle breakdown) during a given workout, but more frequent workouts. So here’s what I suggest. If you’re dissatisfied with the gains you’ve been making in your pursuit of muscle growth, and you’ve been training hard, consistently – take a break first. It’s likely you’ve been over-training. After a few days of rest, start with a new approach. Begin testing how few sets you can do (with more frequency), and still create muscle growth.

Start with a full-body workout, three times per week. Work each muscle with just one exercise, doing about 2 or 3 intense sets (after one warm up set). Do 30 reps on the first set (the warm-up), 20 on the second, 15 on the third and 10 on the fourth – adding weight each set. Rotate the exercises for a each muscle, each time you work that muscle. For example, today you might do flat dumbbell presses for pecs. Next time you work pecs (two days later), you can do incline dumbbell presses. The following chest workout, you can do decline cables…and so on. Try that for about a month.

Then, the following month, you can try doing a two-way split: half the body on Monday, and the other half on Tuesday. Then, either repeat that process (for 3 consecutive cycles, and rest a day), or skip Wednesday, and work the first half again on Thursday, and the second half again on Friday. Skip Saturday and Sunday (or do only cardio exercise on those “off” days). This sort of split will allow you to do 5 or 6 sets per body part (all one exercise, or two exercises) – per workout. Remember – the goal is to stimulate more often, so don’t work a muscle so hard that it requires more than two days or three days (max) of recovery.

You can continue experimenting, if you feel a need to do so. You could try a three way split – 1/3 of the body per day, 8 sets per body part (e.g., 2 exercises of 4 sets each), six days straight, then one day off.

I think you’d get better results with one of these methods, than you would using the previous method of 15 to 20 sets per muscle, per workout, followed by four, five or six days before hitting that same body part again. Less volume (still high intensity per set), but more frequency, makes sense. And it’s certainly worth a try, if for no other reason than that it’s easier. It’s also likely that you’ve been over-training. The more determined (or obsessed) we are to achieve our goals, the more likely it is that we’ll do too much. But training smart is always better than training more.

1. McLester, JR et al (2000), Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 14 (3); 273-81

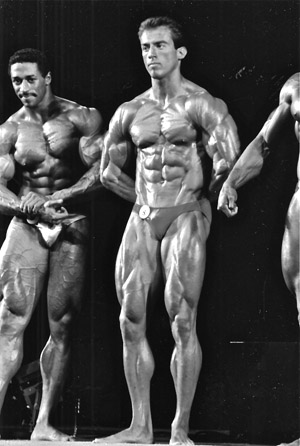

The author, Doug Brignole, winning the Medium-Tall division of the 1986 AAU Mr. America competition

You must be logged in to post a comment Login