There is a segment of the fitness population that believes that “ab crunches” are bad for the spine. Of course, it doesn’t help that the name “crunches” sounds like something that would naturally result in damage. But beyond this, there is a small ripple occurring in the fitness world – possibly instigated by a series of articles (and a book) by Professor Stuart McGill (who, by the way, is notable in his field, but mostly to a sports-specific and a sports-rehab market) – which suggests that the spinal movement involved in ab crunches creates three potential problems:

1. Wearing-out of the spinal discs due to repeated flexing of the spine

2. Herniation of the spine due to over-flexing of the spine

3. Permanent forward flexion in one’s posture due to over-strengthening of the abs, and repeated forward flexing of the spine

I disagree, on all three counts (with the exception of spines that are already injured and are therefore unable to function properly). Here’s my rationale:

First – Some Basic Anatomy & Exercise Science

The function of any given muscle is to bring its “insertion” closer to its “origin” (i.e., its two ends) – thereby creating movement. When muscles shorten (contract or flex), they move a limb or other body part, by bending the joint that they pass. For example, when the biceps contracts, it bends the elbow (because it crosses that joint), which then moves the forearm. Every muscle in the whole body works this way.

The abdominal muscle (rectus abdominus) has its origin at the base of the ribcage, and its insertion at the pubic bone of the pelvis. When the abdominal muscle contracts, it brings the ribcage toward the pelvis, or the pelvis toward the ribcage – which creates a curving (or rounding) of the spine. As the abdominal muscle elongates (relaxes), it allows the ribcage and the pelvis to get farther away from each other – which creates (or allows) the arching of the spine.

It seems obvious that this design – the positioning and function of the rectus abdominus, and the fact that the spine (as a multi-faceted joint) bends forward, to the sides, and backward, as well as having rotation capabilities – is intended for movement in all those directions. In other words, spinal flexion constitutes “normal anatomical function”.

Muscle shortening and elongation is the basis of “isotonic” exercise – which refers to muscle contraction that results in actual bodily movement. When muscle contraction (tensing) occurs without shortening and elongation, it’s considered “isometric”, or “static tension” (when there is no movement at all) or “limited range of motion” (when there is very little movement) – and has been shown in numerous studies to be less effective at developing muscle, as compared to isotonic contraction.

In Reference to Item # 3 (above)

“Rounding the back” occurs when doing an abdominal crunch, but to consider this as “bad”, on the basis that our spine might stay rounded, is like saying that elbow-bending when doing bicep curls is bad, because we don’t want our elbows to stay bent. Backs don’t stay rounded, just because rounding your back is part of the abdominal crunch, any more than elbows stay bent because they did so during a biceps curl.

The idea that a back would stay rounded, on the basis of having the abdominal muscle be “too strong” also makes no sense. Muscles don’t stay in a constant state of contraction, regardless of how strong they are. A relaxed muscle does not contract (or pull) at all, so an abdominal muscle that is super strong, but is relaxed, will absolutely not pull the torso forward permanently.

I certainly agree with the notion that muscles should be in balance. So ensuring that one works their lower-back muscles, to counter-balance the strengthening effects of abdominal exercise, is wise. This is no different than ensuring that one works their hamstrings, as well as their quadriceps; or ensuring that one works their upper back, as well as their pectorals. But the idea of holding back the strengthening benefits of an exercise, on the mistaken belief that a strong rectus abdominus (ab muscle) will pull the torso forward during normal posture, is misguided.

In Reference to Item # 2 (above)

There is such a thing as having the back be “too rounded” during spinal flexion. In other words, one can over-flex (i.e. over-bend) their spine – which would cause the inside edges of the spinal discs to squeeze together, while the outside edges spread open – potentially pushing out the inter-vertebrel discs. This is technically known as “herniation” of the discs.

This is most likely to happen when a person does any kind of lifting with a rounded back (e.g. deadlifts or bent-over barbell rowing), because the resistance that they are lifting (presumably from the ground) is essentially pulling the spine into an over-flex position. But ab exercises are entirely different, because the resistance is coming from the opposite side of the direction that you’re facing. In other words, when the resistance is on the opposite side of your abdomen (you facing up / gravity pulling you back), it would require that the abdominal muscle alone “force” the spine into an over-flex position, and that’s almost impossible to do – even if one tries. It’s about as unlikely to occur as hyper-extending your knees during a heavy leg extension. You would be lucky if you could even get into a full flex, let alone hyper-flex.

In general, I believe that the extreme ranges of motion should be abbreviated. A muscle does not need the beginning 10%, nor the final 10% of the range of motion, in order to reap maximum benefit. I think the center 80% range of motion is the most valuable – and the most safe. However, this depends – in part – on the resistance curve of the particular exercise one is doing. For example, if one is doing a standing barbell curl, it’s safe to allow one’s arms to go all the way to straight (full extension); but allowing one’s arms to go fully straight on a preacher barbell curl is not safe, because the resistance curve of that exercise is such that there is still quite a bit of opposing resistance at full elongation, and it might cause the elbow to hyper-extend, or cause excessive strain to the biceps tendon.

Likewise for abdominal exercise. Extreme arching (or extreme curling of the spine, if one is able actually achieve that, although it’s highly unlikely), is not only not necessary, but also increases the risk of herniation. The issue, therefore, is the DEGREE of movement. Let’s not throw the baby out with the bathwater. Just because it’s not good to over-flex or over-arch one’s spine, does not mean that one should not move their spine at all, as some suggest.

The goal should be to move the spine (during ab exercise) enough to garner the proven benefits of isotonic exercise, but not so much as to pinch the vertebrae (which still allows quite a bit of movement). Therefore, don’t arch your back too far when doing crunches (on a ball, for example). And don’t pull forcefully on your neck, when curling forward. Allowing the typical degree of spinal flexion that normally occurs while “flexing” one’s abs during a crunch, is perfectly safe – I firmly believe. It is within the safe range of motion.

In Reference to Item # 1 (above)

Believing that normal joint movement “wears-out” the joint, reminds me of the adage “a ship in a harbor is safe, but that’s not what ships were built for”. Certainly, crashing a ship against another ship is bad, but that is not “normal” wear and tear. “Sailing” is what ships were built for – and it is “normal” usage, despite the fact that sailing might expose the ship to a small degree of risk. Conversely, keeping it in a harbor – i.e., disallowing normal usage – is unnecessary and unproductive. Further, we don’t skip other normal isotonic exercises (like leg extensions, triceps pushdowns, etc.) because we’re concerned that we might be wearing out the joints, do we?

I agree with the elimination (or restriction) of movements that are not anatomically correct, or require an excessive (unsafe) range of motion. In fact, this is precisely the reason that I discourage people from doing overhead presses (and certain other exercises). But spinal flexion (as in ab crunches) is anatomically correct, and within the safe range of movement.

Worrying about “wearing out” the spinal discs by simply moving them, is like being worried that you’ll wear out your teeth by chewing with them. I would never consider avoiding chewing. But I would certainly avoid grinding my teeth at night, as it would constitute unproductive and improper usage. Eating is part of life. It’s a safe and normal means of survival – even though it might result in a small amount of “wear and tear” on one’s teeth, over the years. The same can be said for spinal flexion.

In Conclusion

Eliminating ab crunches entirely leaves only plank-type exercises, and other static, or limited-range exercises, which are mostly isometric – and are thus inferior to isotonic, for the purpose of achieving visible abdominal development (note: they are useful, however, in certain sports training, if the goal is to be able to maintain a rigid or “stiff” torso while being hit by a 300 lb. lineman on the football field, or in some Mixed Martial Arts applications).

If isometric exercise were equally good as isotonic exercise (or “better-than”, as some proponents of “no crunches” would have us believe), then it would be logical for us to do ALL of our exercises isometrically. Can you imagine doing only “static” exercise for all our body parts? Not curling – just holding a barbell with a bent arm – for example. Not doing triceps pushdowns – just holding a triceps bar static, in one position. Not pedaling a bike – just half squatting against a wall, without movement. I’m sure you get the point.

The function of the rectus abdominus – by definition – is to bring the ribcage and the pelvis closer to each other, upon contraction. Therefore – just as the function of the biceps is to bend the elbow, and we “work” our biceps by bending the elbow against resistance – the way to “work” the ab muscle is to perform its anatomical function (i.e. flexing the spine) against resistance . In fact, this is the reason why the “hanging leg raise” is not a particularly good abdominal exercise – because the movement is not consistent with the rectus abdominus’ designated function. It produces movement of the legs (at the hip joint), rather than of the spine. During a “hanging leg raise”, the abdominal muscles primarily stabilize the torso, while the hip flexors perform the greater part of the movement. By definition, an exercise must perform its function, in order to reap maximum benefit.

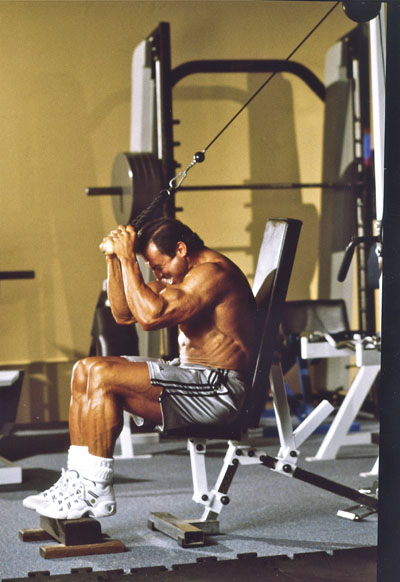

The author performing "seated cable crunches" - seen here in the extended position (photos taken in 2000, at age 40)

The author, seen here in the contracted position. Photos by Michael Neveux

Frankly, I enjoy the feeling of my abdominal muscles contracting (flexing) and alternately stretching (elongating), during ab crunches. It feels very much the way my biceps do during a curl, or the way my triceps do during a cable pushdown. I strive for – and achieve – a deliberate and forceful muscle contraction (resulting in spinal flexion), followed by muscle elongation (resulting in spinal arching), with each repetition.

I also enjoy the wonderful development I’ve achieved from ab crunches – whether I do them by lying on the floor or on a semi-incline bench, or by kneeling on the floor with a cable overhead, or by sitting on a bench with a cable coming from behind. I have no back problems at all. I’m 51 years old, and have been doing various forms of ab crunches for over 35 years.

I’m also extremely sensitive about how my body feels during exercise, inordinately analytical, very well-read on the subject of anatomy and biomechanics, and very pragmatic. I would be one of the first people to cry “foul” – in reference to an exercise – if I felt, or sensed, or thought logically, that something was anatomically incorrect, or unnecessarily strenuous to the body, while doing a particular exercise.

I believe that the hypothetical concern about hurting one’s spine by doing abdominal crunches, has much less of a place in the realm of reality, than does the harm of doing no abdominal exercise at all. By eliminating over-flexing and over-arching the spine (staying within the 80% range of motion – avoiding the last 10% at each extreme), one can safely perform abdominal crunches, without any concern for their spine, and enjoy the reward for their effort – i.e., beautifully developed abdominal muscles.

As I’ve said in the past, training for “fitness” and “bodybuilding” is one thing…. and training for “sports” is another. What improves sports performance does not necessarily improve the physique. Further, each sport requires specific training strategies, for the improvement of that particular sport. “Exercise” is not a catch-all. My focus is on exercise analysis for the purpose of maximizing bodybuilding results (i.e. visible improvements), while minimizing injury risk.

One final word – abdominal exercise of any kind is NOT the key to a fat-free midsection. In general, people spend far too much time doing abdominal exercise, under the mistaken belief that they can “spot reduce” the fat on their gut. It’s not going to happen. A strategic eating plan, cardio exercise, and the overall calorie-spending benefit of resistance training (i.e., enhanced metabolic activity) will gradually reduce the body fat level as a whole, including that of the midsection.

Ab exercises should be done with the same type of frequency, resistance and repetitions, as one would use for any other muscle (biceps, triceps, etc.) – because it works the muscle – not the fat. I recommend 4 – 8 sets of abs per workout, twice per week, for 15 – 20 reps per set, with appropriate resistance.

For more information on a good strategy for a getting lean and muscular midsection, check out my other article, entitled: “Waist Not: The Dos and Don’ts of Getting a Lean Midsection”: http://www.ironmanmagazine.com/blogs/dougbrignole/?p=36.

(photo of Doug below taken at the age of 50)

You must be logged in to post a comment Login