Most of the critiques related to the alleged dangers of eating a higher-protein diet have turned out to exist more in textbooks than in reality. One example is the often stated problem of calcium loss. It’s based on the fact that some amino acids, which are the elemental components of protein, become acidic when they are metabolized, specifically the sulfur amino acids, such as methionine, cysteine and taurine.

Most of the critiques related to the alleged dangers of eating a higher-protein diet have turned out to exist more in textbooks than in reality. One example is the often stated problem of calcium loss. It’s based on the fact that some amino acids, which are the elemental components of protein, become acidic when they are metabolized, specifically the sulfur amino acids, such as methionine, cysteine and taurine.

The increased acidity resulting from the breakdown of the amino acids requires the body to buffer it. Luckily, the body has a few mechanisms to deal with that. One example is bicarbonate, which quickly neutralizes acidity. If the acidity overcomes the bicarb, the body responds by producing hormonal signals that result in calcium release from bones. As such, increased acidity, including from a high-protein diet, can lead to losses of calcium through the urine, as the calcium buffers the acidity and then is rapidly excreted.

The problem is, that scenario doesn’t seem to happen. While there is no doubt that eating a high-protein diet, especially one that is relatively devoid of alkalinizing foods, such as fruits and vegetables, can lead to a type of metabolic acidosis, the excess calcium loss that theoretically should result never occurs in bodybuilders. That’s interesting, since many bodybuilders favor a high-protein, low-carbohydrate diet that lacks fruits and vegetables. So why don’t the bodybuilders lose calcium and show signs of metabolic acidosis?

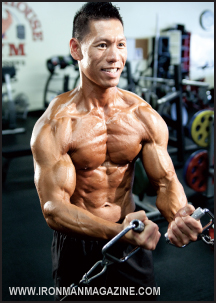

The answer comes in a new study that focused on eight elite Korean bodybuilders, aged 19 to 25, who had won various national bodybuilding championships in Korea.1 All of them had at least two years of training experience. That’s important because most studies often examine untrained college students, whose physiology and reaction to exercise and diets can vary significantly from those of people who have more training experience.

The study was conducted when the men were on off-season diets, meaning that they were eating more food in an effort to gain muscle and strength. That in itself may have influenced the results, since the more calories and food you consume, the greater your chances of getting more nutrients. None of the bodybuilders in the study used anabolic steroids.

The men ate an average of 4.3 grams of protein per kilogram of bodyweight. In contrast, the usual suggested intake of protein for bodybuilders seeking to gain muscle and strength is 1.2 to 1.7 grams, up to two grams of protein per kilogram of bodyweight, or roughly 25 to 30 percent of total calorie intake.

The bodybuilders ate an average of 5,621 calories per day. That’s a lot of calories, but again, these guys were in off-season training and were trying to pack on some muscle. The breakdown of nutrients in the diets was 34 percent carbs, 30 percent protein and 36 percent fat. About 28 percent of the protein came from commercial supplements. The men also took of 2,177 milligrams of calcium and 3,268 milligrams of phosphorus a day.

The bodybuilders showed normal serum glucose and insulin levels. As for kidney function, which is said to be stressed by a higher-protein intake, the men showed BUN scores (a test of kidney function) in the normal range, while another kidney test, creatinine level, was in the upper range of normal. Even so, both of those values were elevated above normal in 25 percent (BUN) and 50 percent (creatinine) of the subjects. Another 25 percent also showed an elevated glomerular filtration rate, which is indicative of increased kidney function. It should be noted that elevations of these kidney tests are related to very high-protein diets and are not considered dangerous to those with normal kidney function. The kidney has the capacity to adapt to such increased protein intakes. Whether that will adversely affect future kidney function after many years of a high-protein diet is still a matter of conjecture.

The men showed normal blood values for minerals, including calcium, phosphate and sodium, but they had higher-than-normal levels of potassium. While not enough be dangerous, the elevated potassium, along with the high calcium levels of the bodybuilders, prevented the metabolic acidosis that would normally have accompanied such a huge protein intake.

Past studies show that supplementing potassium with a high-protein diet prevents the nitrogen loss—as indicated by increased urea excretion—that would otherwise occur with a high-protein diet. That’s based on the fact that potassium is an alkalizing mineral, capable of buffering metabolic acids. Potassium also works with calcium in that regard, helping to prevent excess calcium excretion. Sure enough, the men in the study showed a calcium loss in the upper limit of normal, with normal pH or acidity counts in their urine. Those are indicative of a lack of metabolic acidosis. The authors suggest that intense exercise may also help conserve calcium.

So a combination of a higher potassium intake, a generous intake of vitamins and minerals and regular intense exercise, seems to offset the effects of a higher protein intake in bringing on symptoms of metabolic acidosis, including muscle loss due to excess acidosis.

No Carbs at Night: Another Bodybuilding Fallacy?

The typical bodybuilding diet often prohibits eating carbs past a certain time of day. The idea behind it is that eating carbs when you’re inactive tends to slow down fat loss and may even encourage the gain of additional fat, since the carbs aren’t burned through activity when you are resting. Similar to many other myths in bodybuilding, however, the notion of carb restriction at night may also be just plain wrong.

A new study makes that point.2 Seventy-eight Israeli police officers, all of whom were obese (too many kosher doughnuts?), were randomly assigned to one of two diets. Both diets contained the same number of calories, 1,300 to 1,500 a day, and the same breakdown of nutrients: 20 percent protein, 30 to 35 percent fat and 45 to 50 percent carbs. The only difference was that one group ate the majority of their carbs with dinner, while the other group ate carbs throughout the day.

After six months the subjects eating most of their carbs at night had greater weight loss, smaller waists and greater bodyfat reduction than those who ate their carbs throughout the day. How is that possible? For one thing, eating the carbs mainly during the night changed the way leptin was secreted.

Leptin is a protein secreted by fat cells that sends a satiety message to appetite centers in the brain. In short, turning on leptin decreases appetite. Eating the carbs at night did just that: it raised daytime levels of leptin, which lowered the men’s appetites. The night carb eaters also had several other beneficial changes, such as greater improvements in glucose balance and insulin resistance; an improved lipid profile, including total cholesterol, low-density-lipoprotein and high-density-lipoprotein cholesterol values; and lower levels of various inflammation markers. All of the above would point to a protective effect against metabolic syndrome, which is linked to increased rates of cardiovascular disease and diabetes.

Although eating carbs late at night boosted insulin, it was balanced out by an increase in another fat-protein called adiponectin. While most of the proteins released by bodyfat are inflammatory, which explains why excess fat is so dangerous, adiponectin is one of the good guys. It lowers insulin resistance and boosts fat burning. As you might expect, most people with excess fat stores are low in adiponectin. The increased adiponectin produced by the late-night carb eating raised adiponectin levels during the day while lowering insulin, a scenario that favors increased fat burning. That explains why the cops who ate carbs at night lost more fat around their waists and elsewhere compared to the daytime carb eaters. Having less insulin and more leptin during the day also favors increased fat losses. The rise in adiponectin explains the anti-inflammatory feature of the late-night carb consumption, as well as increased insulin sensitivity.

So should bodybuilders forget the old advice about avoiding carbs at night? Probably. But there is one drawback not discussed in the study. Secretion of human growth hormone peaks at night, especially during the first 90 minutes of sleep. Eating carbs is known to negate GH release, as does elevated insulin. So eating carbs at night will likely blunt GH release. That’s more of a factor for those under 40, since the GH release at night is blunted in older folks anyway. There’s also some doubt that GH release at night provides much fat loss anyway, as it is more effective in that regard when it peaks during exercise.

Editor’s note: Have you been ripped off by supplement makers whose products don’t work as advertised? Want to know the truth about them? Check out Natural Anabolics, available at JerryBrainum.com.

1 Kim, H., et al. (2011). Metabolic responses to high protein diet in Korean elite bodybuilders with high intensity resistance exercise. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 8:10.

2 Sofer, S., et al. (2011). Greater weight loss and hormonal changes after 6 months diet with carbohydrates eaten mostly at dinner. Obesity. 19:2006-2014.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login