How one athlete used the weight room to rehab a major injury in just 30 days.

By Eddie Avakoff, owner of Metroflex LBC

Picture this: You’re an MMA fighter who just came off a disappointing split-decision loss. You fought hard but made mistakes that ended up costing the decision; simple stuff that could easily be fixed. So, with a fire lit under your ass, you show up to practice ready to rock and roll. Training goes well. As you finally begin to shake off the disappointment of losing, thinking you’re going to come out a better and stronger fighter, someone throws your leg too high on a jiu-jitsu guard pass, and you tear your hamstring. Your leg can’t move. In fact, it’s numb from the pain. And just like that, all progress stops. Forget fixing the mistakes from the fight. You need to learn how to walk again.

Welcome to my life this past summer.

There’s a psychological battle at play when you’re trapped in your own body. Watching from the sidelines as others work out is torture. Fitness is my identity, so being stuck in a chair was like being stuck in prison. The crutches that the ER gave me were a constant reminder of my disappointment. I refused to use them. And days following the injury, I limped from doctor’s office to doctor’s office awaiting my MRI evaluations and subsequently, my fate as an athlete.

Every doctor I went to recommended surgery. I didn’t blame them. If I could make 16 grand in an afternoon, I’d recommend surgery, too. And technically the doctors aren’t wrong; a tear exceeding one centimeter usually calls for surgery. However, these doctors didn’t know who they were dealing with. I’m one stubborn SOB.

Surgery was scheduled for a date approximately three weeks post-injury, in case it really was the best recourse. However, I was able to regain minimal movement in my right leg not long after. My zombie limp turned into a stiff walk. And with the ability to walk, I begin to do some sled drags. The sled walks offered slow and consistent eccentric activation, and subsequently blood flow, right to the injured site. Blood carries oxygen and nutrients. I figured that the more blood flow, matched with a nutrient-dense diet, would elicit faster recovery.

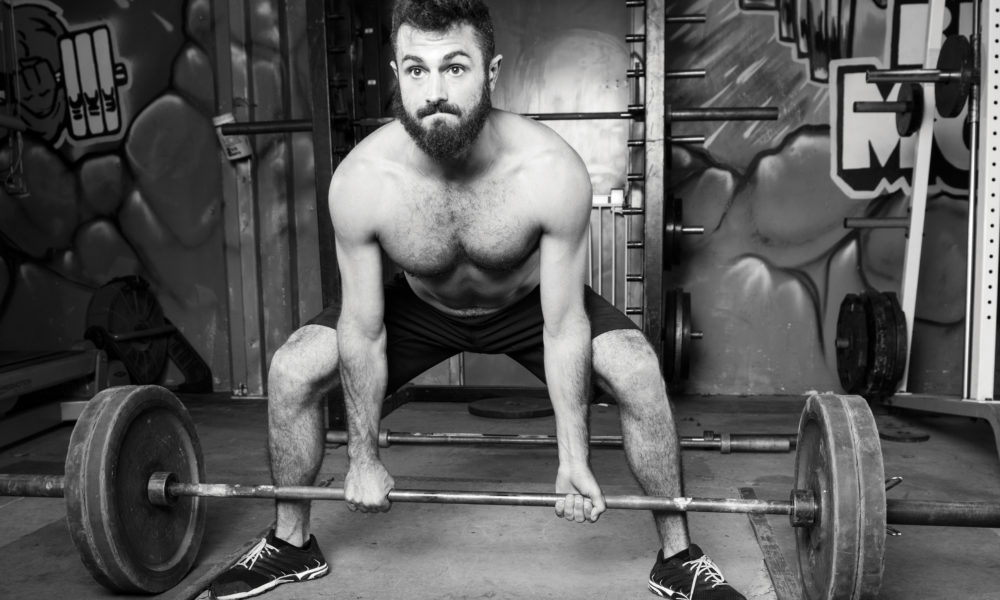

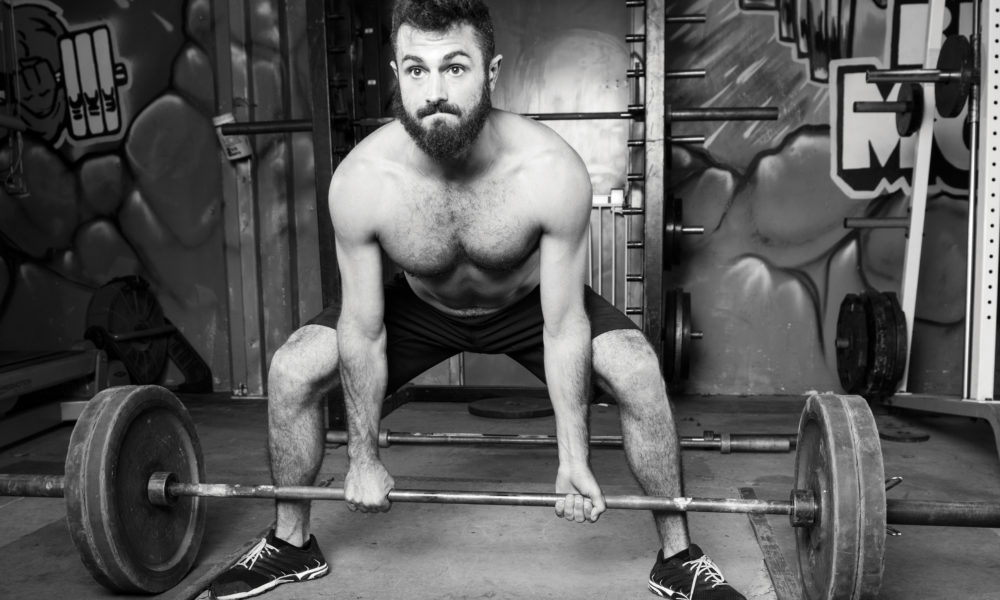

After two consistent weeks of sled walking, the strength in my hamstring was sufficient enough to descend into a high squat (way above parallel, but better than nothing). I also begin to rack pull light weight from about knee height. Any lower would have been too much of a stretch for my hamstring at that time. I’ve always been an advocate of foundational barbell work. Squats and deadlifts are two movements that seem to improve whatever you’re chasing: strength, mass, increased testosterone levels, and even rehabbing an injury. In everyday life, I’ll need to get in and out of chairs and also pick things off the floor, so I might as well start improving those weaknesses now.

For both lifts, I kept the weight light and range of motion limited. The emphasis was on the movement. Speed of each lift was slow but steady. Muscles were squeezed and held tight for the entirety of the movement. Session by session, weight remained consistent, but range of motion increased. I began to descend lower into each squat, and the rack pull height dropped to below the knee and then to shin height. Things were improving!

Lo and behold, my hamstring began to recover even faster with the moderated activation. The stride of my walk returned to normal, and even light jogging began to seem not so far away. Come the day before my surgery, I went to see the doctor. I had to find out: Was surgery really the answer? I felt like it would be taking 10 steps back before taking one forward (figuratively and literally). Upon the doctor’s examination of my hamstring and progress I made, he was astounded: “That leg shouldn’t even be moving yet. I don’t know how you’re walking already.” Not just walking, but at this point, only three weeks after a torn hamstring, I was able to descend into a full squat.

The doctor’s explanation of how I was able to move my leg so quickly came as no surprise: There’s a lot of supporting muscle around the hamstring. That supporting muscle is acting as an “exoskeleton” around the injured site. This supporting muscle is allowing me to move my leg, feeding blood into the injured areas, and thus, speeding up my recovery.

And that’s really what I’m trying to get at in this article: Why rest something if it needs to get stronger? Of course moderation is the key variable that could change something constructive into something abusive. But assuming you’re properly moderating your movements and exertion to ensure everything is constructive, why wouldn’t you want to activate an injured area? Far too often I hear of athletes who suffer an injury and abide by doctors’ orders to rest it. No activation. No movement. Just rest until surgery. And then post-surgery is more rest! Had I taken that route, I would have had to rebuild a lot more than just my atrophied hamstring. My whole body would have gone soft. Out of the question!

Doctors assured me two things as I opted out of surgery: My hamstring strength would be slightly reduced by about two to three percent (however, it would have been reduced by about two percent had I opted for surgery as well) and, more importantly, there was no more susceptible risk of reinjuring that site, surgery or no surgery. So the question really was: “Do I want to be bed ridden for six months?” That was a no-brainer for me.

I respect doctors and their opinions, but sometimes I feel they abide by such caution, they might forget that athletes can heal and recover much faster than someone with a sedentary lifestyle. After all, what really is weight training besides breaking down the tissue and then building them back up stronger than they once were?

I keep telling people, “Exercise is the fountain of youth,” and rehabbing an injury is a perfect example of putting that to the test. Exercise the right way and for the right purpose, and you will be amazed at how your body will respond when given proper food and rest. As I write this article, it’s been about seven weeks since the injury and my hamstring is at about 85 percent healed. My running speed is still slower than it once was, but I can still run. And every week I get faster. Deadlifts are still weak, but I’m still making solid pulls up to about 315 pounds from the floor (I’m usually pulling around 550). I have lots of work to do, but had I undergone the surgery, I would still be facedown in a bed, planning a long road to recovery for 2017. In this case, less was certainly more. IM

You must be logged in to post a comment Login