More athletes get injured while doing the bench press than any other exercise. The two most popular exercises in weight training are bench presses and curls. That’s because all who lift weights for whatever reason want to build impressive upper bodies more than any other bodypart.

More athletes get injured while doing the bench press than any other exercise. The two most popular exercises in weight training are bench presses and curls. That’s because all who lift weights for whatever reason want to build impressive upper bodies more than any other bodypart.

The bench press is indeed an essential part of every strength program for athletes, but it wasn’t always that way. Up until the early ’70s, the lift that determined an athlete’s overall level of strength was the military, or overhead, press. That changed with the emergence of the sport of powerlifting, in which the bench was one of the competitive events.

The military press was knocked out of the top spot mostly because of rumors that it was harmful to the lower back and rather difficult to learn. While that may seem odd, it isn’t because the form for doing a military press perfectly is much more difficult than learning how to bench-press flawlessly.

The flat bench was selected also because it could be done with a minimum of equipment, and countless high schools and some college teams used the benches in locker rooms. Perhaps the main reason that coaches, who usually knew very little about weight training, selected the flat bench over other options was that it was easy to teach. Or so they thought. Certainly it was much easier to teach than any other upper-body exercise.

So it didn’t take very long for the bench press to become the standard of upper-body strength in competitive sports, especially football. The amount of weight an athlete handled in the bench press was suddenly as important as his time in the 40-yard dash. A full ride to a D-1 school is worth a small fortune, so the desire for a big bench was now no longer just for bragging rights—it was the ticket to the future.

That, in turn, placed more pressure on high school coaches to make sure that a great many players posted impressive bench numbers. It would raise their stock considerably in the eyes of recruiters, and that resulted in an “anything goes” philosophy—just get the bar locked out; how doesn’t matter. Excessive bridging, rebounding the bar off the chest, squirming around like an electrified eel and twisting into contortions were not only allowed but were encouraged by parents and coaches. The thought that athletes might be harming themselves—with long-term effects—was irrelevant. If it meant their suffering from a wide array of shoulder injuries down the road, then so be it.

That end-justifies-the-means attitude has caused a lot of problems. Using improper form on any exercise, even simple movements like curls or calf raises, will result in injury eventually. The areas of the body that take the brunt of the abuse from a sloppy bench press are the elbows, wrists, crowns of the shoulders and rotator cuffs.

Yet, when the flat-bench press is done correctly, it’s a useful and safe exercise. Bench presses are one of the best exercises for improving strength in the chest, shoulders and arms. As long as you put form first and don’t overtrain the lift, you should be able to do it for the rest of your life without any problems.

The form points I’m about to make are aimed at those who are primarily interested in doing benches to help them maintain a certain level of strength in their pecs, deltoids and triceps. Their primary goal is not to elevate a huge amount of weight but to stay fit and healthy.

Bench pressing starts with the feet. Sit on the edge of the bench and grind your feet down into the floor. Now tighten every muscle in your body, lie back on the bench, and squeeze down into it. Become part of the bench. That will enable you to establish a solid base from which you can move the stubborn bar through the sticking point.

I know that most coaches teach their athletes to use a wide grip on the bench, but that places a great deal more stress on your shoulders and elbows, so I go with a narrower grip. Extend your thumbs until they touch the smooth center of an Olympic bar. That works for most, but wherever you grip the bar, it’s critical that your forearms stay vertical during the exercise.

Always lock your thumbs around the bar—no false grip, where your thumbs stay next to your fingers. It’s too risky. One slip, and you’re on your way to the E.R. Plus, if the bar runs forward with a false grip, there’s no way to guide it back in the correct line. Make sure your wrists stay locked throughout the lift. Twisting and turning them works against you, as it diminishes the power that your chest, shoulders and arms have generated. If that has become a habit, tape your wrists. It will remind you and help you keep them straight.

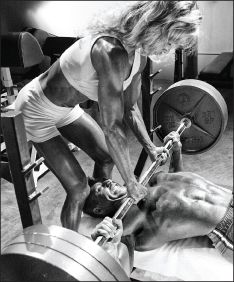

This is one exercise for which it’s wise to have a spotter. Make sure you are in sync with the spotter when he hands the weight off to you and when you rack it at the end of the set. I use a count of three for the start and make absolutely sure the spotter has the bar under control at the finish before I let go.

Take the bar from the rack with your spotter’s assistance, and then pause just a moment to make sure that you’ve fixed it exactly where you want it to be. Take a deep breath, and lower the bar in a controlled manner. Guide it down to your chest so that it touches at the same spot every time. With practice you’ll find the spot that’s not too low or too high and from which you can drive the bar upward with the most thrust.

Pause the bar on your chest for a second. If you make yourself do that from the very beginning, it will save you a lot of grief later on, and you’ll find that you can still handle heavy weights with a pause because you have been making those muscle groups that are responsible for setting the bar in motion much, much stronger.

After the short pause, drive the bar off your chest forcefully. As you’re learning the form, the start can be more deliberate so that you can focus on hitting the desired line of flight every time and making sure that your wrists always stay directly over your elbows. The bar should come off your chest in a straight line, and then it should glide back slightly so that when you lock out your arms, it ends up right over your chin or neck. You don’t want it to wander farther back than that.

As soon as you lock out the bar, exhale and inhale. When to breathe is important. If you’re knocking out 20 reps with a light weight, breathing isn’t a major factor, but on heavy fives, triples, doubles and singles, it’s critical. Breathe only at the start of the lift and at the finish. Even with heavy weights it takes only a couple of seconds to do a bench press rep. Inhaling and exhaling while the bar is in motion forces your rib cage to relax, which, in turn, unlocks your diaphragm. You want your diaphragm to stay locked during any exertion, as that creates a positive intrathoracic pressure, helping you maintain a solid foundation.

Concentrate on using not just good form but perfect form from the very beginning—even with light warmup sets. If you haven’t been doing benches because of some physical problem, you might give them a try again—but move slowly and make form your number-one priority, even if you’re using light-to-moderate poundages. Once you master the technique on this lift, the numbers will take care of themselves. Even more important, all of your improvements will be made safely. —Bill Starr

Editor’s note: Bill Starr was a strength and conditioning coach at Johns Hopkins University from 1989 to 2000. He’s the author of The Strongest Shall Survive—Strength Training for Football, which is available for $20 plus shipping from Home Gym Warehouse. Call (800) 447-0008, or visit www.Home-Gym.com.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login