Before we begin talking about the best Lat exercise, we should first establish a few things – namely, where our Latissimus Dorsi is located, how it’s attached, and what action it produces. This may seem unnecessary to some people – thinking they already know what the Lats do. But I believe once we’ve looked more carefully at these three questions, you’ll see that we’ve been missing the boat (at least a little), in regards to training the Lats with traditional exercises.

While we’re at it, we might as well also identify the other “upper back” muscles (Rhomboids, Infraspinatus, Supraspinatus, Teres Major, Teres Minor and Trapezius), because when we work our “back”, we work all of these as well – not just our “Lats”. But – it’s important to note – the movement that works the Lats, is not necessarily the same as the movement that works the “upper back”. They are essentially two different movements. Let’s focus on the Lats first.

Anatomy of the Lats

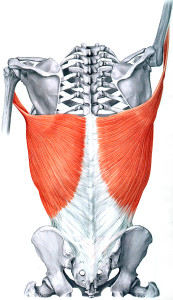

As you can see in the illustration below, the Latissimus Dorsi muscle originates mostly along the spine (technically: the lower six thoracic vertebrae, the lumbar vertebrae by way of the “lumbodorsal fascia”, and the sacral vertebrae), as well as the lower three or four ribs, and the top edge of the Iliac Crest (the upper rear part of the pelvis).

From the illustration below, you can understand why we sometimes see the classic “Christmas tree” shape in the lower back / Lat area. The lumbodorsal fascia does not have the capacity to grow the way the meaty muscle fibers do, so that (upside down V) shape is created when the Latissimus muscle fibers thicken, and rise above the level of the fascia – and a person is lean enough to have that be visible.

In terms of the insertion, you’ll also notice that all the muscle fibers then attach on the underside of the humerus (upper arm bone), high up, a couple of inches from the head of the humerus, near where it inserts into the shoulder socket.

And the final thing I’ll ask you to notice is the direction of the muscle fibers – the upper fibers of the Lats run fairly perpendicular to the torso, and the rest of the fibers fan out (downward), so that the lowest fibers run about a 70 degree angle to the torso.

During any “good” exercise (for any body part), the objective is to stretch and contract the target muscle – to maximally lengthen, and then maximally shorten, the muscle – against resistance. Yes, we want to use enough intensity, enough weight, enough reps, enough fatigue, enough time under tension, etc. – but before we do any of that, we need to first establish that the exercise we’re doing is good – mechanically speaking. Ideally, we want an exercise that involves the proper movement for that muscle, and that the direction of the opposing resistance is correct.

In order to determine the proper movement, we must determine the action that would cause the insertion of the muscle to move directly away from its origin (thereby stretching / elongating the muscle), and then to cause the insertion of the muscle to move back toward the origin (thereby shortening / contracting the muscle).

In order to determine the ideal direction of the opposing resistance, we look for two factors – (1) the resistance should come from an angle that is directly opposite the muscle origin(s), and (2) it should pull in a direction that is parallel to the muscle fibers. Then, when we perform the movement, we will be pulling TOWARD the muscle origins, against resistance.

Recommended Exercise

Therefore, the best way to work the Lats is to perform exercises that provide lateral (outward and slightly upward) resistance, while we pull inward and slightly downward – against that resistance, and toward the muscle origins. In other words, rowing movements are not as good for the Lats, as are “Pull-Ins” (some people are calling them “Brignole Lat Pulls”). This is where one pulls (with one arm, ideally) a cable that is coming from an angle between 60 and 45 degrees, from the side, and we pull the elbow inward, toward the spine, with the palm up. In my view, this is the ideal Lat movement.

Author Doug Brignole teaches rising bodybuilding star Sam Schrader how to perform “Lat Pull-Ins”. Photo by Bill Comstock.

It should be noted that while the Lats certainly participate in rowing motions, they don’t provide as much of a contraction for the Lats as do these “Pull-Ins”, because the humerus (upper arm bone) is moving “back” during a rowing motion, rather than “in” (toward the spine), or down toward the lower Lat fibers. Rowing motions tend to work the upper back more than the Lats. This is due to the direction of the resistance – typically coming from the front, so it’s emphasizing scapular retraction (pulling back of the shoulder blades), more than emphasizing moving the humerus toward the origin of the Lats (the spine).

Keep in mind that the Lats do not pull the shoulders back, because they are not attached to the shoulder blades. They only pull on the humerus (upper arm bone). This is why I said earlier that Lat movement is different than the movement of the upper back muscles. Yes, Rowing movements involve both groups. But if you want maximum Lat stimulation, it’s best to do a PURE Lat movement. Conversely, the upper back muscles do not (primarily) pull the humerus down and in, because their attachments (insertions) are mostly on the shoulder blade, and not so much on the humerus. Their primary function is to pull the shoulders back.

Pulldowns and Pull-ups are better than Rowing (for the Lats), because the direction of the Pulldown movement is closer to the direction of the Lower Lat fibers, than is the direction of the Rowing movement. However, a “straight up” resistance (from Pulldowns or Pull-Ups) is not as good as the direction of movement and resistance provided by Pull-Ins, which is more similar to the actual direction of the Lat fibers.

Anatomy of the Upper Back

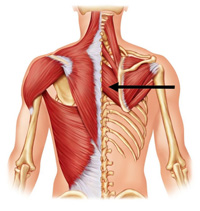

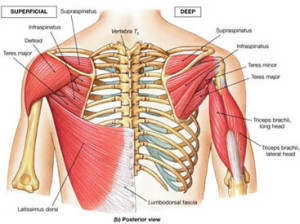

As you can see in the illustration below, there are a number of muscles in the upper part of the back that have their origins or insertions more on the scapula, than they do on the spine, or on the humerus. The photo on the left shows the location of the Rhomboids (note the arrow). The photo on the right shows the muscles of the “rotator cuff”, which are more involved in shoulder movement and arm rotation, than they are in the macro movement of bringing the arm down and in (toward the spine).

The Rhomboids stretch between the spine and the inner edge of the scapula (shoulder blade) – so they do not pull directly on the arm. They pull the shoulder blades toward the spine (scapular retraction) – with the help of the middle fibers of the trapezius (which lay over the Rhomboids).

The Infraspinatus has its origin on the inner (“medial”) edge of the scapula, and its insertion is on the top of the humerus – too high on the humerus, to be effective at pulling the arm – so it also cannot pull the humerus toward the spine. Rather, it pulls the head of the humerus backward, toward the shoulder blade – but mostly it stabilizes the shoulder. This is also true for the Teres Minor.

The Teres Major is better positioned to help pull the humerus downward (because its insertion is lower on the humerus), but it’s obviously not the primary mover of the humerus moving toward the spine, because it does not originate on the spine. These upper back muscles participate more during rowing, and less during pulldowns or pull-ins. They certainly participate when doing rear deltoid work, and when doing external rotation of the humerus.

Summary

For emphasizing the Lats, I mostly recommend doing “Pull-Ins”, and – to a lesser degree – Pulldowns. I think it’s best if the resistance comes more from the side, rather than from straight up. Personally, I prefer one arm at a time, with the resistance coming from about a 45 degree angle from the side. This not only better loads the Latissimus fibers (because the resistance angle matches the direction of the fibers), but it also lessens the risk of “shoulder impingement” (i.e., jamming or forcing the humerus up against the upper / outer edge of the shoulder blade, thereby pinching / irritating the tendons of the Supraspinatus).

If you’ve never done “Pull-Ins”, you’ll be surprised how effective they are. Your Lats will begin cramping almost from the first rep, and they’ll be sore for days afterwards – not to mention the pump! The real value is in having the resistance originate from the side, and only slightly from the front (…I angle my seating position facing slightly to the left when working my right side, and slightly to the right when working my left side). Again, it’s best to keep the palm of the hand facing upward (elbow pointing downward), and really pull that elbow in tightly to your side – imagining that you’re trying to move that humerus straight toward the spine – where most of the Lat fibers originate.

Do rowing movements mostly for the upper back – the muscles that pull the shoulders posteriorly and together. Rowing still works the Lats (of course), but not as much as the exercise(s) that pull the humerus in the direction of the origins of the Latissimus fibers – downward, and inward – toward the spine.

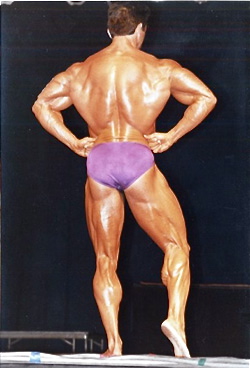

Doug Brignole – seen here in 1991 – is a former state, national and international bodybuilding champion, with a 38-year competitive career. He is the co-author of “Million Dollar Muscle” – a university sociology book.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login