It’s safe to say that all of us were originally introduced to weight training exercises by our predecessors. And our predecessors obtained their information from those who came before them.

We’ve read magazine articles, watched videos, and spoken with those in the gym who appear to be more experienced. They’ve told us which exercises to do – and for which goal – for all our various muscle groups. We followed that advice, and – if we were diligent – we made decent progress. That’s especially true if we had good genetics, and took the appropriate supplements.

The trouble is, since we typically do so many different exercises, we don’t really know which exercises contribute more to our development, and which ones contribute less. The only way to know that for sure, is to do only one exercise for a period of time, measure that progress – and then repeat that sort of evaluation with a different exercise, and then another, etc.

Few of us ever do that. Yet, that doesn’t stop us from giving advice to others – as if we know things “for sure”. What we think we know is “conventional wisdom” – commonly held belief. Ironically, we sometimes defend that belief as if we had personally done a double-blind study, or had done en EMG analysis … never mind that we have not. In fact, all we have is mostly conjecture.

So it is that we have come to believe – in regard to training our pectorals – that we should do incline presses for the upper pecs, decline presses for the lower pecs, and flat / supine presses for the middle pecs.

What if we’ve been wrong all these years ?

Conventional Wisdom for Chest Training

The idea of doing three different angles of presses, for each of the three areas of our pecs, is not without some logic – at least at first glance.

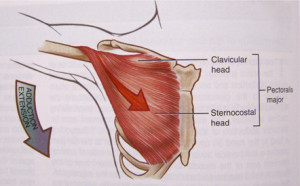

We know that the pectoral muscle has a fan shape. Most of the muscle origins are on the sternum – the center of the torso, on the ribcage. Another small percentage of the fibers originate on the collar bone, and another small percentage of the fibers originate on the cartilage of the lower ribs – mostly the 6th and 7th ribs (i.e., the “lower pectoral fibers”). All the fibers then converge and attach onto the upper part of the humerus (the upper arm bone).

So, it has been conventional wisdom that we should move the humerus in the direction of the fibers, when performing chest exercises – i.e., upward movement for the upper fibers, downward movement for the lower fibers, etc. There’s rarely been any hesitation to say “incline presses”, when someone asks, “what’s the best way to work the upper pecs?”.

However, there is one indisputable rule in biomechanics that – it seems – we have all somehow overlooked.

“Muscles Always Pull Toward Their Origins”

Stand in front of a mirror, and open your arms wide – so that your arms are 90 degrees to your torso. This is the typical position we assume when we “open” our arms during a flat (supine) dumbbell press.

Notice – as you see yourself in the mirror – that your pectoral muscle is entirely below your outstretched arms. There is essentially no portion of your pectoral muscle that is above your outstretched arms.

Now imagine that muscle fibers are ropes. Imagine that you are very small, and you’re holding a “pectoral muscle fiber” rope, as an origin, standing high on a man’s sternum. The other end of your rope is attached to the man’s upper arm bone.

When that upper arm bone swings out, away from you – as this man performs a chest exercise – it “stretches” your rope. Then, it’s your job to bring that upper arm back toward the sternum. When you pull on that rope, you are pulling that upper arm bone directly toward you. You cannot pull in any other direction, other than “directly toward you”.

So, assuming you’re standing at the very top of this man’s sternum – just below his collar bone – in which direction would you pull that arm ? Answer: the same direction you would use if you were doing a flat (supine) dumbbell press. This despite the fact that you are standing at the upper-most part of the “upper pecs”.

In other words, moving the humerus toward a point that is any higher than that (i.e., higher than the highest part of your sternum) – as you would during an incline press movement – would suggest that your upper pectoral fibers have their origin somewhere around your chin, or your nose. Yet, we know that is NOT the case.

Decline is King

Now stand sideways to the mirror, and – with the arm that is farthest away from the mirror – examine what it looks like to move the arm straight out in front of you (perpendicular to your torso)…..then slightly downward….then slightly more downward.

As you can see, moving the humerus in a direction that is toward the center of the pecs (halfway between the upper pecs / clavicle and the lower pecs), creates a “decline” movement. This would allow the greatest number of pectoral fibers to participate in the movement. This places our humerus squarely where most of the pectoral fibers are situated.

If the “King” of pectoral exercises is defined as the one that activates the greatest recruitment of target muscle fibers, the decline dumbbell press would be the King. In my estimation, this is about a 30 degree decline angle.

In addition to providing the greatest recruitment of fibers, the dumbbell press and/or the cable press (or fly) has the advantage over a barbell press, in that it allows a more complete range of motion, which includes a full contraction (shortening) of the pectoral fibers. And – even though I’m not a fan of barbell presses for the pecs (because of the lack of full contraction) – I’d still recommend a decline barbell press over an incline barbell press.

Personal Experimentation

This is a new discovery for me – just a few months ago, in fact. My pecs have always been my most troublesome body part, despite the fact that I’ve tried all the so-called “great” chest exercises (bench press, parallel bar dips, incline barbell and dumbbell presses, etc.). Apparently it’s a genetic thing. How else to explain why some people get great results from the same exercises that produce poor results for others?

Over the last couple of years – wanting to give my upper pecs the optimum amount of stimulation – I doubled down on incline presses. I performed more incline movements than any other kind of chest exercise – almost exclusively. The result? The worst upper pec development ever. “How strange”, I thought.

Suddenly, about three months ago, it hit me. I realized that moving my arms toward my pecs automatically creates a “decline” movement. Moving my arms in an incline direction (toward my head) moves them AWAY from my pecs, because they’re below my arms – not above them !

Throughout my many years of training, I’ve done decline dumbbell presses off and on, but – let’s face it – they’re uncomfortable. First, we have to deal with the fact that the blood rushes to our head. Next, we have to deal with the fact that it’s not easy getting the dumbbells in position to press them (…do we bring them down with us, or do we have someone hand them to us?). Then, there’s the unloading – we have to just drop them. We can’t bring them to our knees when we finish the set, the way we can with incline presses. And there’s no rack onto which we can place them. So, I had avoided them for quite a while for these reasons, but mostly under the belief that I needed to work on my upper pecs more, and that meant inclines.

But now that I see the logic behind doing decline presses, I’ve been doing them exclusively – with outstanding results. In fact – and here’s an irony for you – my upper pecs get more sore with declines presses, than they used to with incline presses ! All parts of my pecs are sore for days after a workout of decline dumbbell presses. Honestly – it gives me a better pectoral workout than anything else I’ve ever done – with absolutely no pain in the shoulder joint. And since it’s the only thing I’m doing, there’s no doubt it’s the declines that are doing it.

Corroboration

A few weeks ago, I was talking with my friend Steve Holman – Editor in Chief at Iron Man Magazine – and I told him about my recent discovery. He said, “Interesting you should say that about declines. Ever since I saw a study that said declines train the entire chest, even the upper section, I’ve always considered it the best exercise for chest.”

It seems a study was done by Barnett, C.,V. Kippers & Turner, P. (1995), whereby an EMG analysis found that incline presses stimulated the upper pectorals no more than did flat or decline presses. Decline presses stimulated all parts of the pecs – upper, middle and lower. Inclines did not stimulate the lower pectorals at all.

I realize that this is only one study, and there may very well be other studies that show entirely different results. So this is not conclusive, by any means.

However, it does make logical sense – that declines are the single best angle from which to work the pecs – since the pecs are “downward” from the arm attachment at the shoulders. Pushing toward the pectorals, and their origins, makes more sense than pushing upwards – away from them.

Conclusion

I’ll be stepping onto the World stage again in June of next year (2014) – having done ONLY decline presses for my chest training for the preceding 18 months. So we’ll see whether or not this little experiment worked. But judging by the way my chest feels now after every workout, and seeing how much progress I’ve made in just this short amount of time, I’d be willing to bet that my point will be proven.

In any event, I encourage you to emphasize declines more – even if you’re not willing to do them exclusively, like me. Just flexing your pecs (while standing) is typically done by moving your arm across your torso, but low – as if you were moving in a decline angle. That should have been the first clue that the decline angle might be the best for maximum pectoral stimulation.

A caveat: there is a small section of the pectoral muscle – known as the clavicular head – that could be stimulated by performing an upward (incline) movement. However, these fibers only represent about 5% – 10% of the total pectoral fibers. And – although they may participate in an upward movement – it appears that they are still worked (very well) while doing flat presses, as well as during decline presses. Plus, these fibers also seem to participate when doing anterior deltoid work (front raises or front presses), as their fibers run in a somewhat similar direction.

Overall, I believe the best angles for training the bulk of the pectorals, are between flat (supine) and a decline angle of as much as 45 degrees. For me, a 30 degree decline angle works just fine.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login